By: Byron Gilliam, Blockworks

once Upon a time,FedThe presidents were free to “teach” politicians’ irresponsible spending habits, and it was a pleasant time.

For example, in 1990, Alan Greenspan told Congress that he would lower interest rates, but only if Congress had to cut the deficit.

In 1985, Paul Volcker even gave specific numbers, telling Congress that the Fed’s “stable” monetary policy depends on Congress cutting about $50 billion from the federal budget deficit.(Ah, that’s really $50 billion in federal debt, not an era of rounding errors.)

In both cases, the Fed chairmen are vaguely threatening the risk of recession in Congress and the White House: You have a good economy now, and it would be a pity if something happens.

However, now the situation is reversed.presidentTrump is “learning” the Fed’s question about interest rates.

Just in recent weeks,TrumpRevealed the federal funds rate “at least 3 percentage points higher”, insisting that there is no inflation, and mocking the Federal Reserve ChairmanJerome PowellFor “Too Late Powell”.

This is also a kind of pressure: you have good central bank independence…

Trump also lobbied for lower interest rates during his first term.Like almost all modern U.S. presidents, he wants the Fed to stimulate the economy.

However, this time, this is much more than that:Trump hopes the Fed will raise funds for the deficit.

The Trump-Powell showdown is ostensibly about current interest rate levels (the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) keeps interest rates unchanged today, which probably would upset the president).

butWhat the president has been threatening is “financial dominance”——That is, the state that monetary policy is subordinate to government expenditure needs.

“Our interest rates should be three percentage points lower than they are now, saving the country $1 trillion a year,” the president recently wrote on Truth Social in its iconic casual capital style.

By making such remarks, Mr. Trump made history and became the first U.S. president to explicitly call for fiscal dominance.

But he is by no means the first to admit this possibility.

This brought the usual hidden link between monetary and fiscal policy to the surface when Volcker and Greenspan threatened Congress with a rate hike.

This worked for them: Both Fed chairs successfully exploited the threat of the recession, prompting Congress to address the deficit spending issue, a promising precedent.

But this strategy seems unlikely to work this time.

Chairman Powell often warns of the risks of growing deficits, even explaining that higher deficits may mean higher long-term interest rates.

But it’s hard to imagine that he would give a clear threat like Volcker and Greenspan – perhaps because he knew he was in a clearly weak bargaining position.

The most worrying impact of rate hikes in the 1980s was the recession, and the Fed was willing to take the risk to prompt Congress to change its spending habits that were big-handed.

At that time, lawmakers faced an ever-inflated defense budget and a stagnant economy, both of which seemed controllable.

Federal debt, which accounts for only 35% of GDP, looks easy to manage.

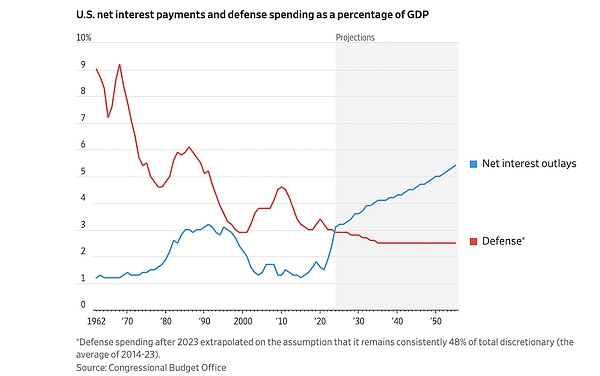

Now,Federal debt accounts for 120% of GDP,The U.S. spends more on interest payments than even defense spending:

<Chart: The rapidly rising blue lines represent the proportion of federal debt interest payments to GDP, far exceeding defense spending>

The fast rising blue line in the above chart is probably the biggest budget issue now.

This puts the Fed in a dilemma: it wants to use the tool of interest rate hikes to “cure” the government’s fiscal problems, but the government’s debt is already so large that interest rate hikes will become “poison” and make fiscal problems worse.

Of course, the Fed can take a chance.

But if the rate hike causes the deficit to rise further, who will blink first: is it the Fed or the White House?

Before answering, consider that 73% of federal spending is now non-discretionary spending, compared to 45% in the 1980s.

If you believe that the Fed won a showdown on deficit, it would be like you believe that Congress is willing to significantly cut non-discretionary spending such as Social Security and Medicare.

It seems, well, incredible.

Especially now, there is a president who seems completely unmoved by the country’s growing debt.

This may have stemmed from his 1990s as aOverly indebted real estate developersexperience.

“I think this is a bank’s problem, not mine.”Trump later wrote about his inability to repay his debts, “What do I care about? I even told a bank, ‘I told you you shouldn’t lend me money, I told you that damn deals simply won’t work.'”

Now, as president, when Trump tells Powell that interest rates should be lower, what he really wants to say is that Treasury is a Fed’s problem, not his.

He said nothing wrong.

“When debt interest payments rise and fiscal surpluses are politically unfeasible,” wrote David Beckworth, a former Treasury economist, “there is a sacrifice.This sacrifice is more debt, more money creation, or both.”

Yes, the Fed can reuse the old trick of Volcker/Greenspan to threaten Congress with higher interest rates.

But Powell probably knows that doing so will only exacerbate a problem that may eventually require the Fed to solve — and accelerate the point in time when it is forced to solve it.

“If debt levels are too high and continue to grow,” Bakerworth explained, “the Fed’s responsibility becomes cater to – by pushing down interest rates or monetizing debt.”

That is the real existential threat to the Fed, he warned, not Trump: “When the central bank is forced to cater to fiscal demand, it loses its economic independence.”

Bakerworth still holds hope, thinking that he may not be able to get there.

Maybe it really won’t.We see how unpopular inflation is, so if there is another round of inflation, voters may force lawmakers to resolve the deficit.

But he felt desperate that focusing on Trump’s demand for lower interest rates was a diversion: “What we are witnessing is not so much about Trump himself, but about growing and inevitable fiscal demand being imposed on the Fed.”

Trump was the first to make these demands explicitly, probably because he knew that the current fiscal policy of the U.S. government is unsustainable.

But everyone knows this, even the government itself knows it.

The only question now is: Who will handle it?