Author: Lyn Alden, investment analyst; compiled by: AIMan@Bitchain Vision

The continuity of the deficit has multiple effects on investment, but in the process it is important not to be distracted by illogical things.

Fiscal debt and deficit 101

Before I dig into these misunderstandings, it is necessary to quickly review the specific meaning of debt and deficits.

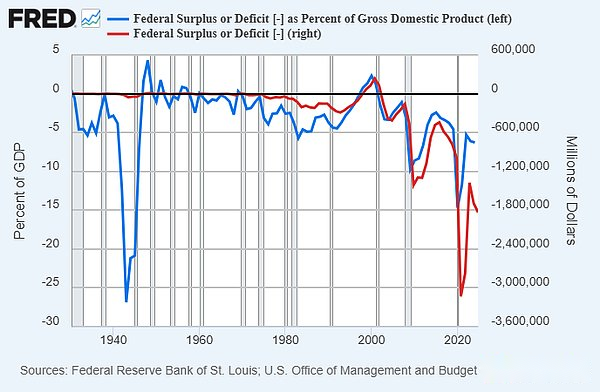

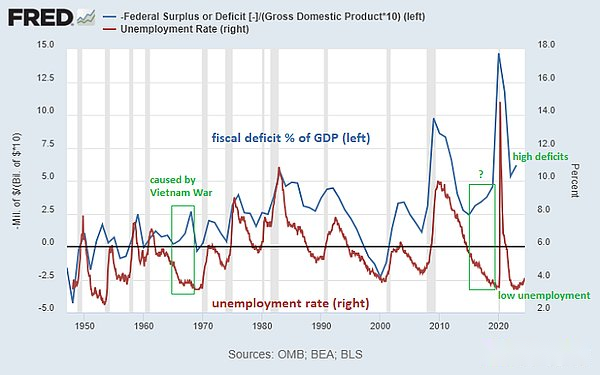

-For most years, the U.S. federal government spends more than its tax revenue.This difference is the annual deficit.We can see the change in the deficit over time from the graph, including the nominal deficit and percentage of GDP:

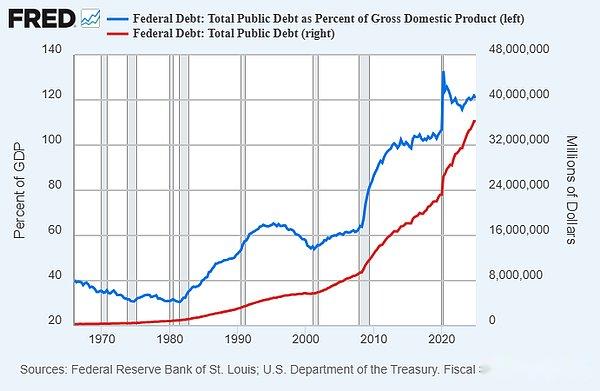

– As the U.S. federal government has been in a deficit for many years, these deficits accumulate to form the total outstanding debt.This part of the debt is the stock of debt owed by the U.S. federal government, and the federal government needs to pay interest.When some of the bonds mature, they issue new bonds to repay the old bonds.

A few weeks ago, at a meeting in Las Vegas, I gave a keynote speech on the U.S. fiscal debt status, a 20-minute summary of the U.S. fiscal debt status.

As that speech and has been elaborated for years, my view is that the fiscal deficit in the United States will be quite large for the foreseeable future.

Misunderstanding 1. This is the debt we owe ourselves

A common saying promoted by Paul Krugman and others is: “We owe our own debts.”Proponents of modern monetary theory often make similar claims, for example, that cumulative outstanding debt is primarily just the total surplus allocated to the private sector.

The implicit meaning behind this sentence is that this debt is not a big problem.Another potential implication is that we may be able to selectively default on part of the debt because it is just “we owe ourselves.”Let’s analyze these two parts separately.

Whom do you owe

The federal government owes U.S. Treasury holders.This includes foreign entities, American institutions, and American individuals.Of course, the amount of government bonds held by these entities is fixed.For example, I owe much more dollars to the Japanese government than I do, even though we all hold government bonds.

If you, me, and eight other people and ten people go out for dinner, we will all owe the debt in the end.If each of us eats differently, then the debt we owe may be different.Fees usually need to be shared fairly.

In the case of the above dinner example, it is actually no big deal, as the dinner crowds are usually friendly to each other and people are willing to generously provide meals to others at the dinner.But in a country with a population of 340 million and living in 130 million different families, this is no small matter.If $36 trillion of federal debt is divided by 130 million households, the total federal debt of each household is $277,000.Do you think this is your family’s worth?If not, how should we calculate it?

In other words, if you have $1 million worth of Treasury bonds in your retirement account and $100,000 worth of Treasury bonds in my retirement account, but we are all taxpayers, then in a sense “we owe ourselves” it is certainly not equal.

In other words, numbers and proportions are really important.Bondholders expect (usually wrong) their bonds to maintain purchasing power.Taxpayers expect (again, often wrong) their governments to maintain a solid fundamentals of their currency, taxes and spending.This seems obvious, but sometimes it needs clarification anyway.

We have a shared ledger and we divide the powers of how this ledger is managed.These rules may change over time, but the overall reliability of the ledger is why the world uses it.

Can we choose to default?

Individuals, businesses and states are indeed likely to default if the debt owed is denominated in currency that cannot be issued (such as gold ounces or other currencies) if sufficient cash flow or assets are lacking to repay the debt.However, the debts of governments in developed countries are usually denominated in their own currencies and can be issued, so nominal defaults occur.For them, the simpler way is to print money, which devalues debts relative to their own economic output and scarce assets.

I and many others will think that a sharp depreciation of the currency is a default.In this sense, the U.S. government defaulted on bondholders by devaluing the dollar against gold in the 1930s, and then in the 1970s, it defaulted on bondholders by completely decoupling the dollar against gold.The 2020-2021 period is also a default, as broad money supply grew 40% in a short period of time, bondholders experienced the worst bear market in more than a century, and their purchasing power dropped significantly relative to almost every other asset.

But from a technical perspective, a country may breach the contract nominally even if it does not have to.Rather than letting all bondholders and currency holders suffer the pain of depreciation, it is better to default only on unfriendly entities or entities that are capable of bearing, thereby broadly protecting currency holders and non-defaulted bondholders.In such a tense geopolitical environment, this is a possibility worthy of serious consideration.

So the real question is: Are there situations where some entities have limited consequences for default?

Some entities will have very serious and obvious consequences if they default:

– If the government defaults on debts from retirees or asset management companies holding government bonds on behalf of retirees, then this will damage their ability to support themselves after working for life and we will see older people taking to the streets to protest.

-If the government defaults on insurers’ debts, it will weaken their ability to pay insurance claims, thus harming U.S. citizens in the same bad way.

-If the government defaults on the bank, the bank will lose its ability to repay debts and consumer bank deposits will not be fully supported by the assets.

Of course, most entities (the surviving entities) will refuse to buy Treasury bonds again.

All that remains are some easier to achieve.Are there entities that governments can default on, which may be less harmful and do not endanger survival like the above options?The possibility usually lies in foreign companies and the Federal Reserve, so let’s analyze it separately.

Analysis: Delinquent debts from foreigners

Currently, foreign entities hold about $9 trillion in U.S. Treasury bonds, accounting for about a quarter of the total $36 trillion in outstanding U.S. debt.

Of the $9 trillion, about $4 trillion is held by sovereign entities and $5 trillion is held by foreign private entities.

In recent years, the possibility of defaulting on specific foreign entities has undoubtedly increased significantly.In the past, the United States has frozen sovereign assets in Iran and Afghanistan, but these assets are small and extreme and are not enough to constitute any “real” default.However, after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the United States and its allies in Europe and elsewhere have frozen Russian reserves totaling more than $300 billion.Freeze is not exactly the same as a default (it depends on the ultimate fate of the asset), but is very close to a default.

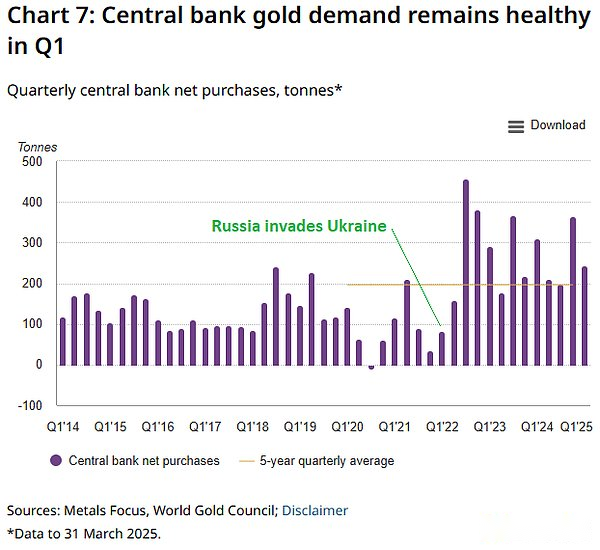

Since then, foreign central banks have become quite large gold buyers.Gold represents an asset they can keep on their own, so it can avoid defaults and forfeiture, and it is not easy to depreciate.

The vast majority of foreign-holding U.S. debt is held by friendly countries and allies.These countries include Japan, the United Kingdom, Canada, etc.Some of these countries, such as the Cayman Islands, Luxembourg, Belgium and Ireland, are safe havens, where many institutions set up institutions and hold U.S. Treasury bonds.So some of these foreign holders are actually American entities incorporated in these places.

China currently holds less than US$800 billion in government bonds, which is only equivalent to the US’s five-month deficit expenditure.They are at the top of potential “selective default” risks, and they are aware of it.

If the United States defaults on such entities on a large scale, it will greatly weaken the United States’ ability to convince foreign entities to hold their national debts for a long time.The freezing of Russian reserves has sent a signal, and countries have reacted to it, but at the time they were under the guise of Russia’s “factual invasion”.Debt defaults on non-aggressive countries will be considered as obvious defaults.

Therefore, overall this is not a particularly viable option, although in some cases it is not impossible.

Analysis: Fed defaults

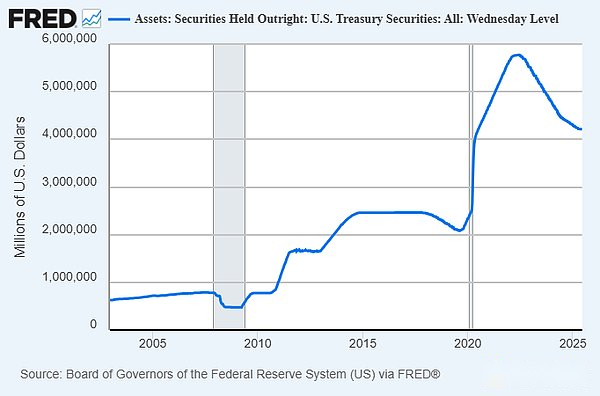

Another option is that the Treasury Department may default on U.S. Treasury bonds held by the Federal Reserve.Currently, the Federal Reserve holds slightly more than $4 trillion in US Treasury bonds.After all, this is the most appropriate statement of “we owe ourselves”, right?

This also has major problems.

The Fed, like any bank, has assets and liabilities.Its main liabilities are 1) physical currency and 2) bank reserves owed to commercial banks.Its main assets are 1) U.S. Treasury bonds and 2) mortgage-backed securities.The Fed’s assets pay interest on it, while the Fed pays interest on bank reserves to set a lower interest rate limit, curbs the motivation for banks to lend, and create more broad money.

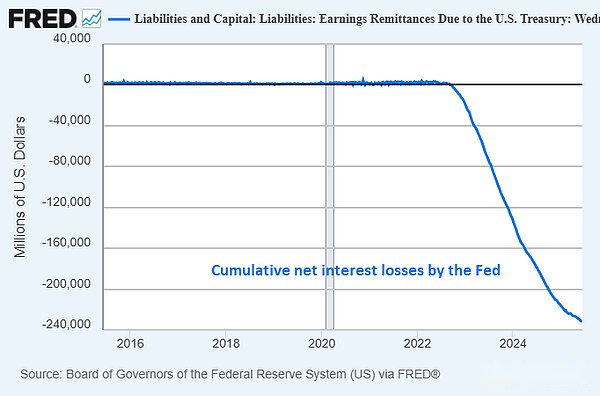

Currently, the Fed is suffering huge unrealized losses (hundreds of billions of dollars), with weekly interest payments far higher than its revenue.If the Fed was an ordinary bank, it would definitely suffer a run and eventually go bankrupt.But since the Fed is a central bank, no one can run it, so it can operate at a long-term loss.Over the past three years, the Fed has accumulated net interest losses of more than $230 billion:

If the Treasury Department completely defaults on the Fed’s debt, it will be seriously insolvent at the real exchange rate (the liabilities will be trillions of dollars more than assets), but as a central bank, they can still avoid bank runs.Their weekly net interest loss will be even greater, because by then they have lost most of their interest income (because they only have mortgage-backed securities left).

The main problem with this approach is that it will undermine any philosophy about central bank independence.The central bank should be basically separated from the executive branch, for example, the president cannot cut interest rates before the election, raise interest rates after the election, or make similar pranks.The president and Congress appointed the Fed’s board of directors and gave it a long term, but since then the Fed has its own budget, which should usually be profitable and self-sufficient.A defaulted Fed is an unprofitable Fed and has huge negative assets.Such a Fed is no longer independent, and even the fantasy of independence is gone.

One potential way to alleviate this problem is to remove interest on bank reserves paid by the Federal Reserve to commercial banks.However, there is a reason for this interest.This is one of the ways the Fed sets a lower interest rate limit in an environment with abundant reserves.Congress can pass legislation: 1) Force banks to hold a certain proportion of assets as reserves; 2) cancel the Federal Reserve’s ability to pay interest on these reserves to commercial banks.This will turn more problems to commercial banks.

The last option is one of the more feasible ways, and the consequences are relatively limited.The interests of bank investors (rather than depositors) will be damaged, and the Federal Reserve’s ability to affect interest rates and bank loans will be weakened, but this will not be a disaster overnight.However, the federal deficit held by the Federal Reserve is only equivalent to a federal deficit of about two years, accounting for about 12% of the total federal debt. Therefore, this slightly extreme financial suppression plan can only play a “oint” role to temporarily alleviate the problem.

In short, we do not owe ourselves debts.The federal government owes debts to specific entities at home and abroad, and once defaults, these entities will suffer a series of consequential damages, many of which will in turn harm the interests of the federal government and U.S. taxpayers.

Misunderstanding 2. People have been saying this for decades

Another thing you often hear about debt and deficit is that people have called it a problem for decades, and things have been good.The implication of this view is that debt and deficits are not a big problem, and those who think they are important will end up being “calling the wolf” over and over again, and therefore can be ignored with confidence.

Like many misunderstandings, there is a certain truth here.

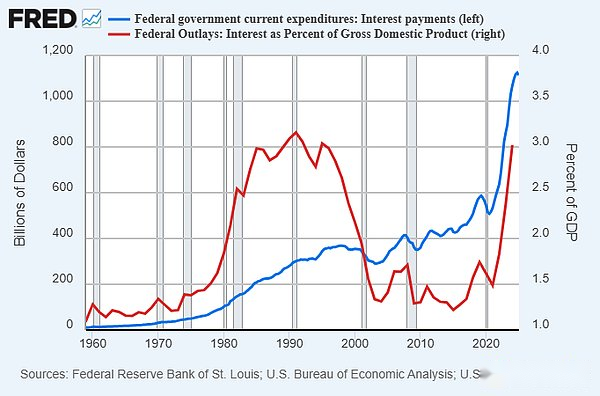

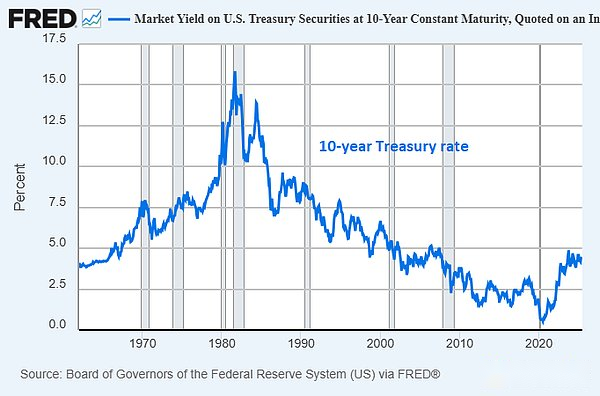

As I pointed out before, the “zero-spirit pinnacle” of the view that federal debt and deficits are problematic dates back to the late 1980s and early 1990s.The famous “Debt Bell” was erected in New York in the late 1980s, and Ross Perot’s most successful independent presidential campaign in modern history (with 19% of the popular vote), largely revolved around the theme of debt and deficit.At that time, interest rates were very high, so interest expenses accounted for a high proportion of GDP:

Those who thought debt would be out of control at the time were indeed wrong.Things have been good for decades.There are two main things that lead to this situation.First, China’s opening up in the 1980s and the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s had a very serious deflationary impact on the world.A large number of Eastern labor and resources were able to connect with Western capital, bringing a large number of new commodity supplies to the world.Second, interest rates have continued to fall due in part to these factors, which makes interest expenses on the growing total debt in the 1990s, early 2000s and 2010s more controllable.

So yes, if someone had said debt was an imminent question 35 years ago and was still talking about it today, I can understand why someone would have chosen to ignore them.

However, people should not think too far and think that since this matter does not matter during this time, it will never matter.This is a fallacy.

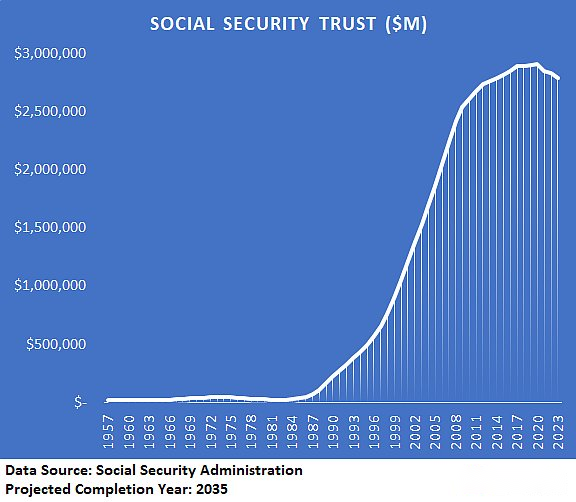

There were multiple trend changes in the late 2010s.Interest rates fell to zero and are no longer in a structural downward trend since then.The baby boomers began to retire, resulting in the peak of social security trusts and entering a reduction mode, globalization also reached a potential peak, and the three decades of interconnection between Western capital and Eastern labor/resources have basically ended (and may be slightly reversed now).

Some trend changes are visualized as follows:

We have not reached the point where debt or deficits will cause massive disasters in the near term.However, we have entered an era where deficits do have impacts and consequences.

For six years, after witnessing some early stages of trend changes, I have always emphasized that fiscal spending occupies an increasingly important position in modern macroeconomic and investment decisions.It has been my main “North Star” as I move forward in this rather chaotic macro environment for years.

Since these trend changes began to happen, taking debt and deficits seriously has been a great way to: 1) not be surprised by some of the things that have already happened; 2) manage portfolios more successfully than a typical 60/40 stock/bond portfolio.

-My 2019 article “Are we in the bond bubble?”》 is the preface to this paper.My conclusion is, yes, we may be in the middle of a debt bubble, the combination of fiscal spending and central bank debt monetization may be more influential and inflationary than one might think, and that is likely to happen in the next recession.In early 2020, I wrote “The Subtle Risks of Treasury Debts”, warning that Treasury Debts could depreciate severely.In the 5-6 years since that article was published, the bond market has experienced the worst bear market in more than a century.

-At the worst of the deflation shock in March 2020, I wrote the article “Why This Is Different from the Great Depression” that highlights how large fiscal stimulus (i.e., deficits) begin and may bring us back to nominal stock highs faster than one might think, although it could cost high inflation.

Over the rest of 2020, I have published a series of articles, such as Quantitative Easing, Modern Monetary Theory and Inflation/Deflation, A Century of Fiscal and Monetary Policy, and Banking, Quantitative Easing and Money Printing, which explores why the powerful federation of fiscal stimulus and central bank-backed is completely different from the quantitative easing policy of bank capital restructuring in 2008/2009.In short, my argument is that it is more like war financing in the inflation-era period of the 1940s than private debt deleveraging in the deflation-era period of the 1930s, so holding stocks and hard currency would be better than holding bonds.As a bond short, I spent a lot of time debating this topic with bond longs.

By the spring of 2021, the stock market had risen sharply and price inflation did begin to explode.My May 2021 newsletter “Financial-Driven Inflation” further describes and predicts this issue.

In 2022, as prices reach their peak and fiscal stimulus measures during the epidemic gradually become ineffective, I have become quite cautious about fiscal consolidation and potential recession.My January 2022 newsletter, Capital Sponge, was one of my early frameworks for this scenario.Most of 2022, in terms of broad asset prices, was a bad year and the economy slowed down significantly, but by most indicators, the recession was avoided due to what started to happen later that year.

By the end of 2022, especially at the beginning of 2023, the fiscal deficit has expanded again, largely due to the rapid rise in interest rates, which has led to the inflation of public debt interest expenditures.The Ministry of Finance’s ordinary accounts draw liquidity back to the banking system, and the Ministry of Finance turns to issuing excess treasury bonds, an initiative that favors liquidity, aims to pull funds back to the banking system from reverse repurchase tools.Overall, deficit expansion has once again “war”.My July 2023 newsletter titled “Financial Lead” focused on this topic.

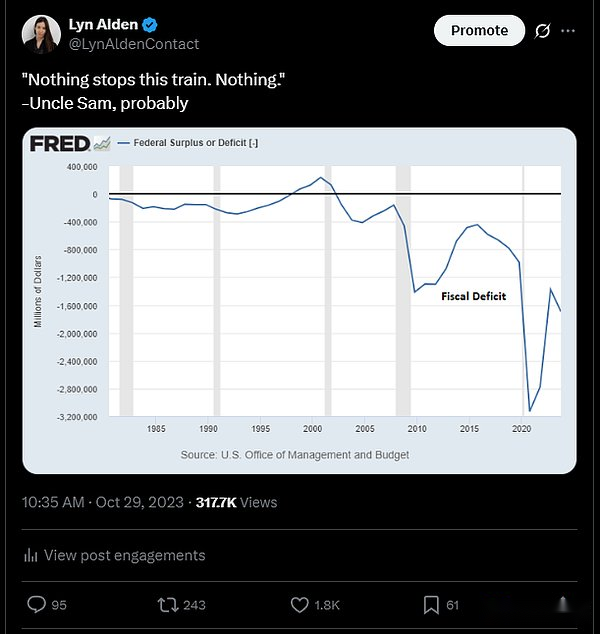

– October 2023, the federal fiscal year 2023 (from October 2022 to September 2023) has ended, and the nominal deficit has increased again, and I started the meme of “Nothing can stop this train” with this theme (originally from the TV series Breaking Bad, but here is referring to the U.S. fiscal deficit), and my tweet is like this:

I keep highlighting this because it effectively expresses the key points:

My point is that we are in an era where total debt and ongoing federal deficits have a real impact.Depending on whether you are suffering from these deficits, you may feel that the effects of these deficits are positive or negative, but they will have an impact anyway.These effects are measurable and reasonable and therefore have an impact on the economy and investment.

Misunderstanding 3. The US dollar is about to collapse

The first two misunderstandings contradict the general view that debt is not relevant.

The third is a little different because it refutes the idea that things will explode tomorrow, next week, next month or next year.

Those who claim that things will break out soon are often divided into two camps.People in the first camp, they benefit from sensationalism, click-through rates, and more.People in the second camp really misunderstood the situation.Many in the second camp did not conduct in-depth analysis of foreign markets and therefore could not really understand the real reason for the collapse of the sovereign bond market.

The current deficit in the United States accounts for about 7% of GDP.As I have pointed out many times, this is mostly structural and it is difficult to significantly reduce now or in the next decade.However, deficits account for 70% of GDP are not a problem.Scale is important.

Here are some important indicators that need to be quantified.

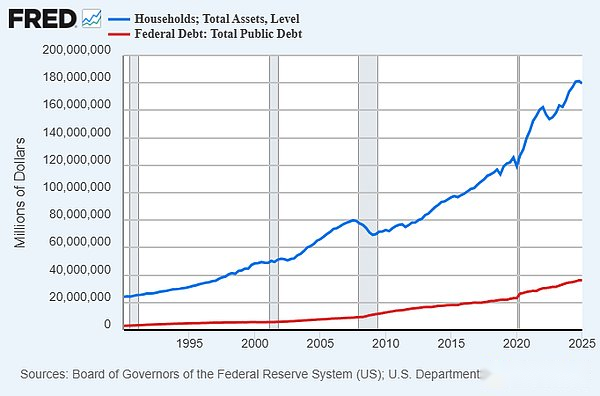

-The federal government’s debt is slightly higher than $36 trillion.By comparison, the total assets of American households are $180 trillion, and after deducting liabilities (mainly mortgages), the net assets are $160 trillion.However, since we don’t owe ourselves, this comparison is a bit like apples and oranges, but it helps to look at the huge numbers in a more specific context.

The US monetary base is about $6 trillion.The total outstanding U.S. dollar-denominated loans and bonds (including the public and private sectors, domestic and international sectors, excluding derivatives) exceeds $120 trillion.In the overseas sector alone, the dollar-denominated debt is about $18 trillion, three times the existing base dollar.

This means that the demand for the US dollar at home and abroad is extremely huge and cannot be flexible.All U.S. debt holders need US dollars.

When countries like Türkiye or Argentina experience hyperinflation or are close to hyperinflation, the background is that few people need their lira or peso.There is no deep-rooted demand for their currency.So if their currency becomes less popular for any reason (usually due to the rapid growth of money supply), it is easy for people to deny it and send its value to hell.

This is not the case with the US dollar.All of these $18 trillion foreign debts represent a rigid demand for the dollar.Most of them do not owe the United States (the United States is a net debt country), but foreign countries do not “owe themselves”.Countless specific entities around the world owe a certain amount of dollars to countless other specific entities around the world by a specific date, so they need to keep trying to obtain dollars.

The fact that they owe a total of more than the existing base dollar amount is crucial.Because of this, the monetary base can double, triple or even more without causing complete hyperinflation.This is still a small increase in contract demand for USD.When outstanding debts are far exceeding the base dollar amount, a large amount of base dollar is required to make that base dollar worthless.

In other words, people seriously underestimate how much the U.S. money supply can grow before it triggers a real dollar crisis.Creating politically problematic inflation levels or other issues is not difficult, but creating a real crisis is another matter.

Think of debt and deficit as a dial instead of a switch.Many people will ask “When will it matter?” as if it were a light switch that would go from no problem to disaster.But the answer is, it is usually a dial.It is now very important.We are already running passionately.The Fed’s ability to regulate the growth of new credit has been damaged, leaving it in fiscal dominance.But the rest of this dial still has a lot of room to turn before it actually reaches the end.

That’s why I used the phrase “Nothing can stop this train”.The deficit problem is more tricky than bulls think, meaning the U.S. federal government is unlikely to hold them in the near term.But on the other hand, it is not as imminent as bears think; it is unlikely that it will trigger a complete dollar crisis in the near term.It was a long and slow train wreck.A pointer is gradually turned.

Of course, we may encounter a small crisis similar to the 2022 UK Phnom Penh bond crisis.Once that happens, hundreds of billions of dollars can usually be put out at the cost of depreciation.

Assume that bond yields soar to the extent that bankruptcy or severely inadequate liquidity in the U.S. Treasury market.The Fed can take measures to quantitative easing or curb yields.Yes, this brings the price of potential price inflation and has an impact on asset prices, but in this case it does not trigger hyperinflation.

In the long run, the US dollar will indeed face major problems.But there is no indication that there will be catastrophic problems in the near term unless we are socially and politically divided (this is not related to the data and therefore not within the scope of this article).

Here is some background information.Over the past decade, the US broad money supply has increased by 82%.During the same period, Egypt’s broad money supply increased by 638%.The performance of the Egyptian pound is also about 8 times depreciating the US dollar; ten years ago, the US dollar was slightly lower than the 8 Egyptian pound, and now, the US dollar was slightly higher than the 50 Egyptian pound.Egyptians faced double-digit price inflation for most of the decade.

I live in Egypt for a while every year.Life there is not easy.They often experience energy shortages and economic stagnation.But life has to continue.Even that level of currency devaluation is not enough to put them in a complete crisis, especially with institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF), who can basically only continue to walk on the path of increasing debt and devaluation of currency.

Imagine how inflexible the dollar’s demand is, how much it would cost to put the dollar into that situation, let alone a worse situation.When people think the dollar is about to collapse, I usually assume they have not been to many places and have not studied other currencies.Things may be much more serious than people think, but they can still partially work.

More data shows that China’s broad money supply has increased by 145% over the past decade, Brazil has increased by 131%, and India has increased by 183%.

In other words, the US dollar will not directly change from a developed market currency to a collapsed currency.In this process, it must experience “developing market syndrome”.Foreign demand for the US dollar may weaken over time.The ongoing budget deficit and the growing control of the Federal Reserve may lead to a gradual acceleration in the growth of the money supply and financial suppression.Our structural trade deficit gives us monetary vulnerability that countries with structural trade surplus do not have.But our starting point is developed markets with deep-rooted global network effects, and as the situation worsens, our currency may be similar in many ways to the currency of developing markets.For quite some time it may be more like the Brazilian currency, then the Egyptian currency, then the Turkish currency.It will not jump from the dollar to the Bolivar of Venezuela in a year or even five years unless there is an event like a nuclear strike or a civil war.

To sum up, the rising debt and deficit situation in the United States is indeed having increasingly realistic consequences, both in the present and in the future.It is not as negligible as the “Everything is OK” camp claims, nor is it as soon as the sensational camps claim to be disaster.It is likely to be a thorny issue and will be bothering us as a background factor for quite some time, and investors and economists must take this into account if they want to make accurate judgments.